An Emoji Story

Two years ago, when generative AI began to flood the internet and our daily applications, many designers surely found themselves in the same predicament as I did: what pictogram or icon should be chosen to symbolize this trend? Circuit boards or brains made of computer cables seemed reductive, even outdated, failing to convey a sense of innovation, wonder, and enchantment.

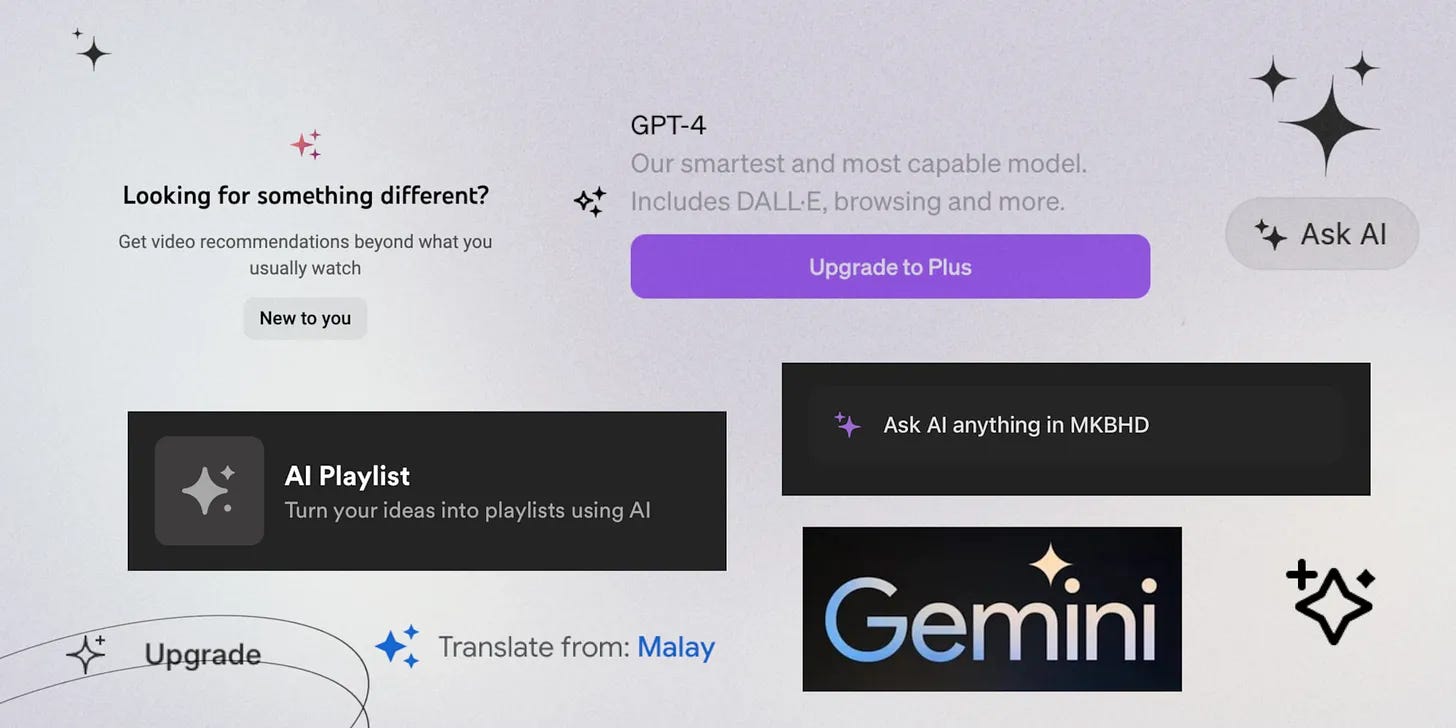

Then suddenly, almost everywhere, simultaneously, several major software programs began to adopt an emoji whose initial use was never intended to represent a technological revolution: the Sparkles emoji (✨). This emoji, which has existed since the very first sets of pictograms designed by the Japanese artist Shigetaka Kurita in 1999, has long had a vague meaning, allowing for its adoption through subjective interpretation across the world, a form of digital vernacularity shaped by cultures and countries. This excellent YouTube video traces the origins of this adoption, and another article exploring the birth of this tacit convention suggests the reason for its adoption: “It can seem like magic if you don’t understand how it works,” said Jane Solomon, the senior emoji lexicographer at Emojipedia.

And that’s precisely the point I want to address: the illusion of magic and the problems it creates. This enchanting argument has a major impact (and clear benefits) for the tech giants.

Magic as a Feature

The use of the concept of magic by Big Tech companies is nothing new. It doesn’t take much digging into the communications of tech giants like Google and Apple to uncover their obsession with simplicity (embodied by Google’s homepage and Steve Jobs’ minimalist design philosophy), minimizing friction for users to guide them seamlessly, while eliminating choices available to them.

“It just works,” Apple proclaimed as early as the 2000s, with the firm intention of making us forget our questions, and with them, our ability to examine our decisions and our alternatives.

This notion is evident in the launch of the iPhone, when Steve Jobs announced this “feature”: “It works like magic.” He reiterated this at the launch of the iPad, describing it as a “magical and revolutionary device.” Subsequently, a range of products was born: the Magic Mouse, Magic Keyboard, and Magic Trackpad.

Google followed more recently with its generative AI tools for photo editing in the Pixel 8: “Magic Eraser” and “Magic Editor,” marking one of the first uses of this famous Sparkle emoji (✨). Was it inherited by the Magic Wand of Photoshop? But for some people, they definitely buried the era of the photography as a medium of trust, as noted by The Verge, inaugurating the age of “Everything is Default Fake” as defined by Ruby Justice Thélot in this great piece.

The massive adoption of the Sparkle emoji as a symbol of AI’s glittering promises thus entrenches a universal sentiment about technology: the normalization of a form of mysticism surrounding this new algorithmic revolution.

We Are All Apprentice Sorcerers

There is something key about generative AI in this ambiguous relationship we have with the models surrounding us: the prompt.

If ChatGPT exploded so quickly to reach one million users in five days, it’s likely because language is the most natural and simple interface, regardless of culture or country. This echoes an older instinctive belief: we almost enter the realm of incantation, the original word that gave life, the source of creation. A divine power and a specificity of our humanity and our capacity for consciousness. When we prompt, our words give birth to an image, a text, a video.

This creative capacity is at the heart of many spiritualities, but also of most esoteric practices, where the magic formula, the sacred word, is key. Abracadabra! This word, known to all, has a controversial origin, possibly Aramaic, derived from the words “evra kedabra,” meaning “I will create as I speak.”

The prompt becomes a kind of performative formula, which, once spoken, brings to life what was said. This incantatory power has never been so powerful, and here we are, all Creators, in the demiurgic sense, a kind of magical transcendence that allows our will to finally be embodied.

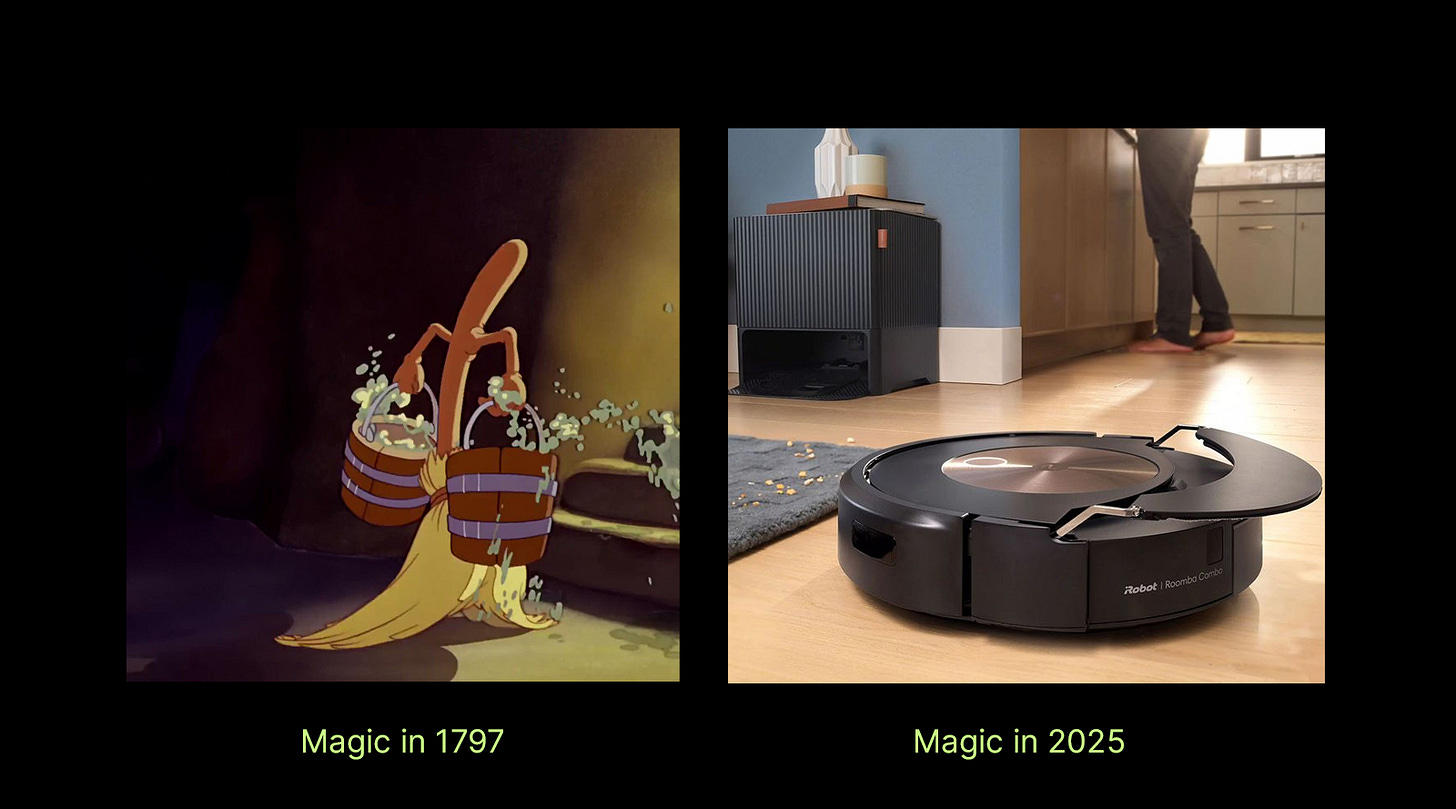

Goethe already warned us in his poem about the sorcerer’s apprentice, a key myth visually popularized by Fantasia. Except that the automation of tasks has already been mostly achieved, and it is this touch of consciousness, of understanding, of intelligence, which has remained out of reach… until now.

There’s no doubt we are so quick to marvel at the possible sentience of generative AIs, where our anthropomorphic relationship to these systems pushes us to marvel without being alarmed by the hubris lurking behind this desire to create an alterity more intelligent than ourselves, the holy grail of AGI pursued by all. The fact that it is a black box even for the researchers themselves is what enables this technology to confuse humans so effectively.

The Relationship Between Tech and Esotericism

“AI began with an ancient wish to forge the gods”

Pamela McCurdock - Machines Who Think.

If we trace back the history of AI, an interesting anecdote described by Mitchell Marcus involves three major pioneers of AI. Joel Moses, Gerald Sussman, and Marvin Minsky all worked at MIT in the 1970s, renowned researchers in this emerging field. During a party, one of them recounts that his grandfather, at his Bar Mitzvah, had passed on an incantation to awaken the sleeping golem of Prague, the very one created by Rabbi Loewe, who was one of his direct ancestors.

Gerry Sussman, amused, announces that his grandfather had given him the same recommendation, and the two colleagues leave to exchange the inherited incantation. It turns out that Minsky had also received the same prediction but was annoyed by the mysticism of his colleagues and claimed not to give it any importance.

Sussman would later say about this anecdote:

“Computer scientists are the Kabbalists of today”

This anecdote interests me because we often think that science and religion are incompatible. Max Weber, a German sociologist, already mentioned in 1917 the role science played in the “disenchantment of the world", pushing back mysticism and beliefs, which for the most part were incompatible with scientific rationalization.

However, even if one might think that the worlds of science and mysticism are two opposing universes, certain tech circles have long had a particular attraction to high art and alternative spiritualities. Whether some call it cybercraft, cybermagick, technoshamanism, or technopaganism, many esotericism enthusiasts base their practices on these new tools.

“So if you choose to venerate Snap (the God of microwaved foods), Click (the computer mouse Goddess), Popup (the Goddess of toasters and toaster ovens), Ram and Rom (the computer twin Gods), Bit and Byte (the computer twin Goddesses), or Wireless (the spirit of cell phones), go for it!”

Patricia Telesco and Sirona Knight - Magick in the Virtual World

One could explore these practices for a long time, but that would take us away from our topic. For those interested, I refer you to this interesting essay by Venetia Robertson or the famous book of Erik Davis’s, TechGnosis.

Nonetheless, these practices exist, and this collusion between innovation and occultism regularly appears in Silicon Valley’s history, whether in AI or other spheres (Nick Land, the father of Accelerationism, had a rather dark attraction to occultism, going so far as to live with members of the CCRU in Aleister Crowley’s house, the famous black mage from the last century).

The technophiles engaging in this “reenchantment of the world” and this ontological shift, generally do so with a superior knowledge of how these tools work. They are not the credulous ones but the sorcerers, the wizards, the ones who possess the knowledge.

“Every society has its magician, its illusionist. This function in modern society is now occupied by the Techno-Evangelist.”

For the general public, however, the “magical” dimension, announced with much marketing fanfare, is mainly a way to promise easy, pre-chewed, and often addictive use of a revolution that is magical in name only.

From mythical to mystical

However, this is not the first time in the history of technology that technical innovations have been linked to a form of superstition or even a belief in a higher power, as Nick Susi notes in his great essay exploring this subject.

"Every New Wave Of Technological Innovation Is Accompanied By Magical Thinking."

Nick Susi - Magic, Online!

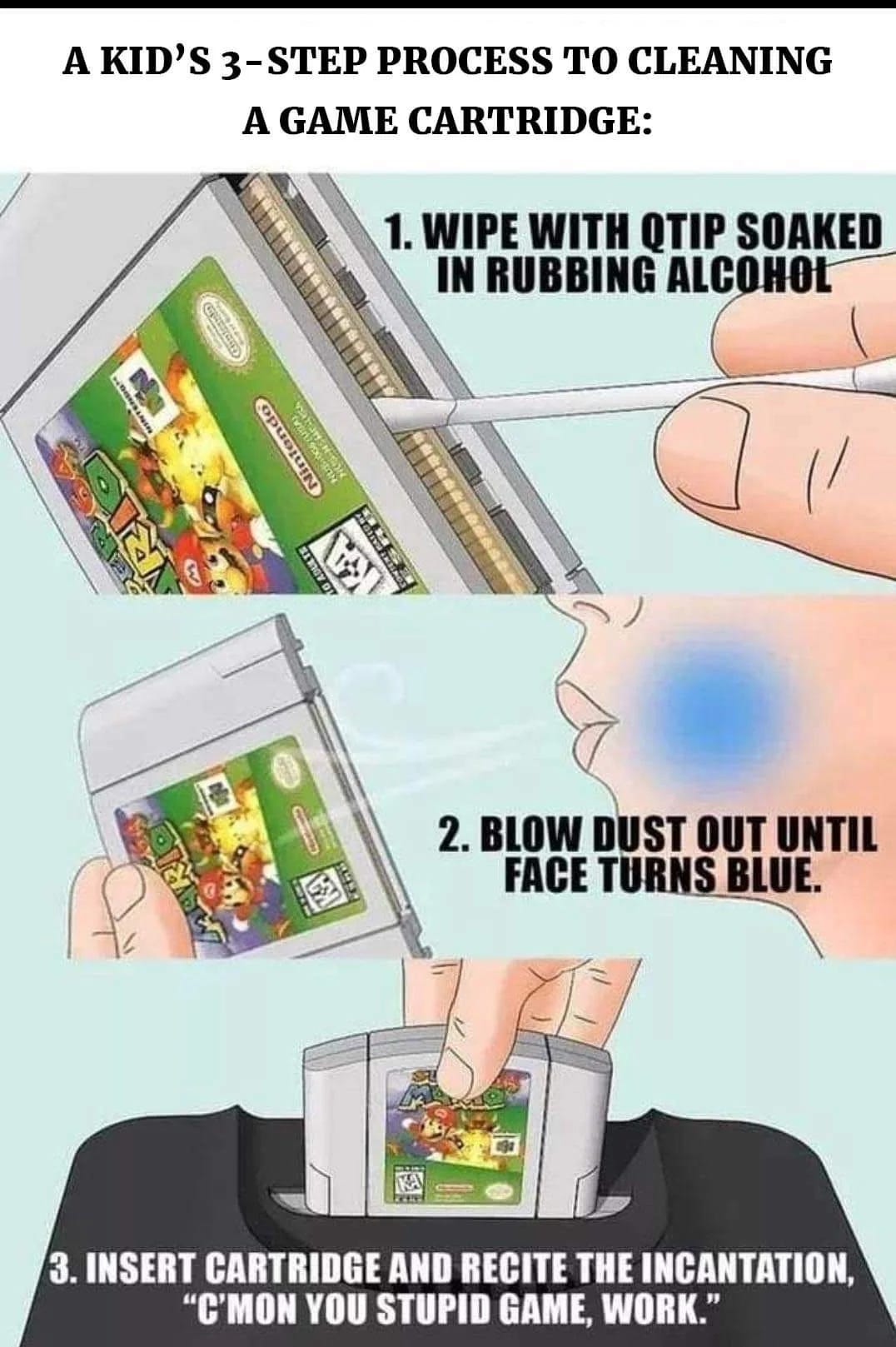

We might laugh at the everyday superstitions of our ancestors, but they have endured and evolved into the present day. We have all been influenced by unfounded beliefs and urban legends that drive us to perform unnecessary actions (blowing into video game cartridges, closing smartphone apps, an amusing list of entirely pointless gestures).

However, there is a major problem with turning our technical misunderstandings into beliefs. Failing to understand how a technology works, no matter how advanced, is disempowering: we hide behind our ignorance to avoid understanding and reflecting on its functionality and the impact of our use.

The technological object thus becomes a form of myth.

Media theorist Neil Postman, in a 1998 lecture, already discussed this idea in relation to technological change, drawing inspiration from Roland Barthes' approach:

"When a technology becomes mythic, it is always dangerous because it is then accepted as it is and is therefore not easily susceptible to modification or control."

This echoes what Barthes had already implied: the use of myth by elites to control the masses, notably by imposing a concept that depoliticizes the true meaning of the object.

Russian artist Olia Lialina elaborates on the term "technology," which is already a limiting abstraction:

"The word technology was pushed on us to unempower us as computer users. It was pushed by the industry that smartly calls itself high tech, and we started to use the word technology instead of other words that would be empowering: computer, algorithm, interfaces, hardware, software, program."

It must be admitted that understanding technological objects and mastering them requires time, knowledge, and effort. This necessary friction to maintain control is precisely the main obstacle exploited by tech giants to retain dominance over our digital habits, preventing us from questioning in detail the potential negative impact of these new uses.

The semiological choice by these companies to appropriate the lexicon and imagery of magic is thus entirely deliberate, demonstrating a long-assumed marketing strategy and a desire to obscure the workings of these innovations.

Fighting the Occult

Among the early adopters of generative AI, who are generally far from being tech illiterates, how many truly understand how an LLM or a diffusion model works?

Who can analyze the original datasets, comprehend how they were labeled, grasp the differences in representation proportions, detect biases, or better yet, mitigate them?

By hiding the functioning of their innovations, companies that claim to revolutionize the internet of tomorrow sweep under the rug all the labor necessary for training these models, including the click workers who contributed to their refinement, as well as the cost in rare materials, energy, water, and carbon that every query and chip require.

Maintaining this illusion of magic severs users from a holistic vision of the impact of these technologies. They are not merely tools, as many like to proclaim, but rather a means to alter our environment and ourselves, as Heidegger described with his concept of Gestell, or as other theorists have also explained.

"We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us."

Marshall McLuhan

From Abstract to Tangible

I am part of a generation that grew up with the tangibility of the internet, its physical manifestation, whether through the network speed of the first modems, whose connection through the telephone cable was a constant reminder of this invention’s physical limitations. Similarly, the first 256MB MP3 players, eMule, and hours of downloading that remained stored locally, or the cost of SMS, limited in terms of characters.

The "cloudization" of the web has had a perverse effect: creating the illusion of infinity, of a space so informal that we no longer realize that data, streams, and information are indeed physically processed and hosted.

This myth of the inexhaustibility of our resources, a corollary to the issue of technical misunderstanding, is, in my opinion, even more dangerous. This form of technological cornucopianism, which implies that infinite growth in these material resources is possible, is a necessary dishonesty for tech giants.

To have a chance to return to a form of digital sobriety, we must first become aware of it to even consider it. Understanding how the digital world around us operates is essential to grasp the near and distant implications of our usage. And perhaps we will avoid endlessly prompting unnecessary questions whose answers can be found in a dictionary, which consumes far less energy.

I remain convinced that it is crucial to educate and teach our children from an early age the basics of coding, how the internet is structured, issues of data flows and servers, and the impact our technological choices have on us and our environments. We risk a greater digital divide than ever before, and tech illiteracy is becoming a key issue of our individual sovereignty.

The big question, when we are so surrounded by technology and its benefits, yet still recognize its shadows and problems, remains as follows:

How can we imagine a more nuanced, reasoned approach to our digital usage, one that is more human and conscious as well? This delicate path lies between outdated Technocriticism and unbridled Accelerationism.

Perhaps that’s partly why I write. To try to imagine other paths. Or to inspire some.